By Vince Brandon

1. Introduction

There is a long-standing belief that the act of coaching is more of an ‘art’ than a ‘science’ and given the lack of domain specific scientific information available for our sport it appears that general practices are obtained by osmosis from other casting geeks. We cannot change that process unless there is a sudden injection of research funding into fly casting, therefore we can only hang on to the coattails of other sports to ensure that we are teaching best practice. With spare time on my hands due to Covid, I’ve continued to practice the casting skills that got me through the assessment. During the darker hours, I am using my spare time looking at various sports coaching topics to become a better instructor.

To generate a framework, I have started my analysis from what I call the casting system, which is not only the tackle that we use but also includes the individual who uses it to produce the desired outcome. My casting system considers how the commands to move are structured, the sequences that dispense the commands and the feedback mechanisms that regulate and correct those commands. To put my casting system structure on a sounder footing, I have considered the component parts as scientific disciplines and believe that the underpinnings of fly casting instruction are based in the physics of casting mechanics, biomechanics and the science of motor learning and control.

Casting Mechanics

Although it has failed to eradicate the mythology, the instructosphere has put a considerable amount of effort into replacing some of the more arcane theories of casting mechanics with a better understanding of how for a given input the rod and the line produce a desired output. For anyone starting down this path, I would recommend “The Rod and the Cast” by Grunde Løvoll and Jason Borger and “8 rods for 8 Casters”, both of which are available from the Sexyloops site. Rod builders and instructors may also be interested in “Measuring Swingweight” by Grunde Løvoll and Magnus Angus.

If you follow any of the various fly casting discussions on the ether, you will be well aware that there are many mechanics treatments out there and I do not see any great value in revisiting the topic in detail here. As a systems engineer, I would always advocate laying out your requirement before jumping to a solution. My requirement is to have a tool that allows me to understand the mechanical principles of casting because it is incredibly useful for fault finding. That model needs to enable me to isolate the potential causes of a faulty cast and must be in a form that I can carry in my head. This last requirement is essential because it needs to function in the casting environment and produce answers in near real time. It is not a problem for me if you are asking an entirely different question that drives the generation of a more complex model because we all need a tool that is fit for purpose. Consequently, I don’t intend to revisit the topic again, except in passing or by accident.

Biomechanics

Having worked my way through a Biomechanics Foundation course, I found enough similarity with my day job skills in the non-medical elements that I felt comfortable with the modelling and verification elements. I would be very reluctant to go to print on anything associated with the biological side because of the medical implications of getting it wrong. Instead, I have limited myself to working through the specific fly casting literature, including some very good papers on biomechanics as it relates to casting injuries. As a starting point, I would suggest searching for the article “Overuse Injuries in Fly Fishing: Recognition and Injury Prevention” by Sherman, Taylor and Sherman, then working your way through the reference section of the paper.

For absolute casting performance, there is also a paper on haul timing that is excellent “An Initial Study on the Coordination of Rod and Line Hauling Movements in Distance Fly Casting” by Ulrik Röijezon et al and I would also suggest a trip to Mark Herron’s TheCuriousFlyCaster site to delve into some easily digestible material. The latter is one of the few places where you will encounter discussion of any sort on fly casting skills acquisition by motor learning and control and that is where I will try to focus my attention. Whilst there are some unique control aspects such as hauling and mends, I am starting from the premise that casting is primarily a throwing activity and throwing any object over a distance requires fine control of either a rotational or translational velocity that is generated by a kinetic chain. Consequently, drawing parallels from throwing sports should be a profitable activity that is worthy of investigation.

Methodology

In producing this text, I have reviewed a sample of the common literature available to other sports, drawn parallels with the fly casting world and offered some solutions based on my limited practical experience. I am aware that there are other related topics and more material out there, some of which I will return to at a later date.

2. Dealing with Pressure – Performance Anxiety for Casters

Why and What

Have you ever suffered from performance anxiety? Few people like to discuss perceived shortcomings it but it’s one of the most commonly reported symptoms of social fear. James wrote a great article about it as a Sexyloops Front Page that was discussed on the Board and shared on Facebook.

If you look at the responses to his article, it would appear that nobody else in the world of casting suffers from the same thing…. except maybe me. Nevertheless, it is possible to see the effects of performance anxiety not only in competition casters but also instructors undergoing assessment or casting in front of their peers and particularly in students undergoing lessons. I would also suggest that it is not unusual even in people trying to target a particular fish in front of their friends. Many of us have failed when conducting tasks that are usually effortless but are performed badly just because somebody may be watching. Judging from the response to James, few people will publicly admit that they have suffered when conducting a public demonstration of a skillset.

If you look at any other similar endeavour in the world, the effect of performance anxiety on motor control is well documented and vast resources have been poured into studying the phenomenon. Sports has its own term – “chokers”. There’s a stigma attached with choking. Nobody wants that label and people are reluctant to talk openly about this common phenomenon. However, a quick search on the internet will provide reams of psychological and medical information detailing the causes and effects of performance anxiety on a wide range of sports but none that specifically addresses fly casting.

Different Sports with Common Problems

Golf and fly casting are technical sports where the action take place in a short space of time compared to the duration of the activity. The actions in both sports are deliberate, requiring accuracy of movement to produce a desirable outcome. The comparatively long breaks between the casting stroke or golf shot allows plenty of time for the outside world to encroach on the casters/golfers thoughts or allow the individual to dwell on a particular aspect of his performance and distract them from the task in hand such that accurate and smooth movement is impaired. The golfing industry in particular has investigated the causes of these distractions and proposed strategies to address these internal and external distractions.

“The Sport Psychiatrist and Golf” by Clark, Tofler and Lardon is well worth reading for its top level summary of the available literature. In Winning, the Psychology of Competition by Walker it is suggested that if a player is investing his sense of self-worth in the outcome, it becomes more difficult to win. Renowned golf coach David Leadbetter proposes that the challenge of how well a player focuses on the shot at hand, rather than being taken off-task by thoughts, emotions, or poorly controlled physiological arousal is fundamental to success. He calls this “mental chess.” There are clear parallels for James and I to consider. We are both distracted by the simple act of setting up a video to record ourselves casting, even if there is nobody there to witness how many attempts we take to deliver a good cast.

Emotional Arousal in Sport

Talking about changes in physical skills to improve performance in casting is commonplace but we rarely address why an individual’s performance drops off under pressure. This is because it is easy to move a student’s feet to fix a tracking error but unravelling the emotions in the top two inches of their skull is fiendishly difficult.

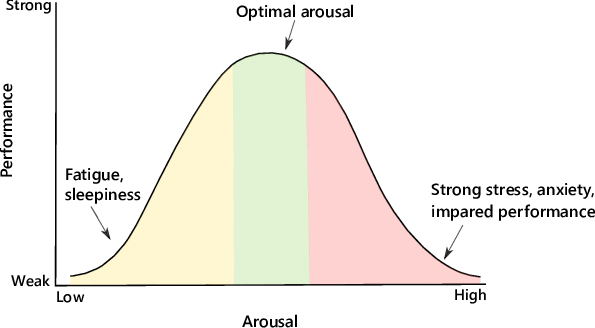

Dr. Rajpal Brar’s article for Grand Central called “Why Athletes Choke Under Pressure” analyses how pressure/stress affects movement and thinking/memory. The article describes the Neuroanatomy system in an understandable fashion and explains how the nervous system manages sensations, movement, motor control and motor learning. It then discusses how pressure and stress can interfere with fluent movement. He proposes that an individual’s state of arousal is based upon Yerkes-Dodson law that posits that there is an optimal level of arousal for performing tasks as shown in the figure below:

In common with the golf specific articles he states that “Motivation and aversion to loss come in many forms: winning the game, monetary incentive, emotional happiness or sadness and also in the form of protecting upholding our self-image”. The higher the personal stake the further to the right of the scale you are likely to be. I have certainly been in that red zone during assessments due to “over-arousal” caused by an aversion to failure.

Emotional Arousal in Casting Instruction

I suspect that most novice casters have low expectations for their initial casting lesson. After all, few people expected to be able to ride a two wheel bike at their first attempt and far fewer actually achieve immediate success. A more complex problem is trying to understand why an experienced caster would part with his hard earned money. What are his expectations? The most favourable case is that the individual has reached a plateau and wants to extend their existing skills or learn a new one, or they may have a genuine problem that they want to fix. In all of these instances, their ego may be a little fragile and require careful handling but you probably have a handle to work on in these cases, provided that their core skills are sound. Unfortunately this is often not the case and as a coach you may need to take them two steps backwards before you can take them forward.

You have also to be prepared for the fact that this piece of bad news may not be well received and is made more difficult because so many lessons are single shot activities. Consequently, you may have had little opportunity to establish a rapport with your client and if not handled carefully you may never see the client again and your professional reputation could be damaged. Your own confidence might suffer a bit if you receive negative or no feedback back from your clients. The risk that the client ego can be bruised and your professional reputation damaged can be mitigated to a certain degree by prior preparation and careful management. In the worst case, either one of you can come unravelled by the pressure of the situation; you for your failure to teach a skill or your student by being unable to grasp your instruction.

The Death Spiral

Syed describes choking as “as a kind of neural glitch that occurs when the brain switches to a system of explicit monitoring in circumstances when it ought to stick to the implicit system. It is not something the performer does intentionally; it just happens. And once the explicit system has kicked in (as anyone who has been afflicted by choking will tell you), it is damned difficult to switch out of”. This death spiral of failure is something that we also need to have strategies to avoid in lessons, assessments and competitions. These strategies could be as simple as stopping for a drink, changing over to teaching an entirely new skill or even handing over the student to another instructor. Delaying a decision to change the structure until it is too late can be very damaging if the relationship between the student and instructor is irrevocably broken.

Understanding and mitigating the risk in lessons

Having identified the risks we need to develop mitigations. Instructors have to create that nurturing environment in very short order with students who are often total strangers and get them operating in that green zone. Risk aversion is deeply embedded in many people, they will not expose themselves to public failure unnecessarily and our students are taking a leap of faith when they come for a lesson. Taking them to a public place for a lesson is already one step towards exposing their insecurity and we may not get the best from them, so we need to consider the environment. They will need time and space to explore how they put together the complex body movements to draw a straight line with a rod tip. It is likely that they have practiced a similar skill painting a wall with a brush or roller without having a dot to dot picture drawn for them. We also need to be aware that we may appear very intimidating to the student because our demonstrations are based on skills that have taken hundreds or thousands of hours of practice to become proficient. Moreover, our slick, jargon heavy explanations may sound as remote to them as a lecture on quantum physics does to me. We need to be particularly aware of our own interpersonal skills.

In preparing our lessons we need to provide achievable goals, monitor the relationship and create a comfortable space to allow the student to achieve the desired outcome. For me that means nudging the student towards a successful outcome and protecting their ego, rather than focusing on failures. The lesson plan should be flexible enough to modify those initial goals because it is essential that the student leaves with a victory under the belt or it is likely they will never practice those skills again. Providing the student with a deliberate practice plan to take away is the only chance that they will take those conscious tasks you have taught them and transfer them to automaticity. Unless the coaching relationship is long term, that practice is the only route to eventual success for your student.

I suspect many instructors conduct their lessons either by a blend of rote, cloning successful methods from other instructors or based on their own personal learning experience. We should continually question and check that our teaching styles are robust and agile enough to deliver a lesson that protects the student from overwhelming failure. When guiding, I have taken a student from the field having learnt to cast reasonably proficiently and watch their newly acquired skills dissolve through cognitive overload 30 minutes later because they are now also learning line control whilst casting to a rising fish. Workload management is key to a successful outcome and they will watch you for cues. Make sure they leave you feeling good about themselves.

Learning from experience

Having failed instructor assessments, I have tried to put myself under repeated and controlled stress to try to desensitize myself to performance anxiety. However, it has been a long and bloody road to get this far. It is not easy to repair your bruised ego after failure. Many of us aspiring casters invest our sense of self-worth in the outcome of public demonstrations of competence whether it is in assessments or competitions. However, I have found that many of those casters that are at the top of their game have managed to put aside their egos and seek external input if they think that there may be value in that alternative view, even if it is offered by someone less proficient. I particularly recall being at a Game Fair where two master casters were supporting a tackle manufacturer and were just idly casting to fill the time between punters. One of them noticed a tracking error in the other and muttered the observation to his colleague, who made corrections until it was confirmed the problem had cleared. I also see a similar attitude in many competition distance casters but believe that I have to work to obtain that state of grace.

In reviewing the underpinning science, I’ve found that it is possible to identify instructors who are using these techniques and are consistently obtaining good outcomes. In my experience, the successful instructors are also very aware of the emotional state of the student and construct an environment that relieves the student’s self-induced pressure. The success of these instructors is partly down to individual personality but is also the product of prior preparation because they are constructing and maintaining a learning environment that gives the student the optimum chance of success.

Fear of failure is inbuilt and it appears that few instructors will publicly admit to having delivered a catastrophic lesson or admit to having found students that they cannot teach. Consequently, the instructional world seems slow to learn from experience. Mentors to aspiring casting instructors face a different problem; they have longer to develop the skills and can challenge the student much more but the investment in the end result is much higher, depending on whether the student passes or fails. How to deal with failure also does not appear to be openly discussed. Coming from the aerospace industry, I find it odd that failures are not objectively dissected because that is how we strive to remove systemic safety errors and this open culture is strongly encouraged. Indeed, failing to highlight a problem is considered a greater evil than actually making a mistake in the first place.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You must be logged in to post a comment.